Introduction:

Solar radiation is the primary force behind forest growth, providing the energy trees need to sustain their metabolic functions. Through photosynthesis, trees capture sunlight and convert it into chemical energy, fueling essential processes such as leaf expansion, wood formation, and root development. However, not all trees interact with light in the same way—species vary in their ability to absorb and utilize sunlight efficiently, shaping the structure and composition of forest ecosystems.

The Role of Sunlight in Tree Growth

Solar radiation is the driving force behind forest growth & forest ecosystems, providing the essential energy needed for tree growth and development. Through the intricate process of photosynthesis, trees convert sunlight into chemical energy, which fuels their metabolic activities, from leaf expansion to root elongation. However, trees have evolved to utilize light in diverse ways, adapting to the specific environmental conditions in which they grow.

Some species, known as light-demanding trees, thrive in open landscapes where they receive uninterrupted sunlight, enabling them to maximize photosynthetic efficiency. Others, classified as shade-tolerant species, are adept at surviving beneath dense canopies, making efficient use of limited light resources. The ability to adapt to varying light conditions significantly influences species distribution, forest composition, and competition dynamics within an ecosystem.

Photosynthesis Efficiency and Shade Tolerance

Sunlight is the fundamental driver of photosynthesis, yet different tree species exhibit varying levels of efficiency in utilizing light. This distinction leads to their classification into three primary categories based on light requirements:

Tree Type | Examples | Preferred Light Conditions |

Light-Demanding (LDS) | Teak, Pine | Full Sunlight |

Shade-Bearing (SBS) | Beech, Hemlock | Partial to Full Shade |

Shade-Demanding (SDS) | Mahogany, Fir | Deep Shade, Canopy Cover |

(Source: FAO, 2020)

- Light-Demanding Species (LDS): These trees, such as teak and pine, require direct exposure to sunlight for optimal growth. They grow rapidly in open environments and are commonly found in early-successional forests or plantations where competition for light is minimal.

- Shade-Bearing Species (SBS): Trees like beech and hemlock have adapted to grow in moderate light conditions, often flourishing beneath taller, light-demanding species. They exhibit greater photosynthetic efficiency at lower light intensities, allowing them to persist in partially shaded environments.

- Shade-Demanding Species (SDS): Some trees, including mahogany and fir, are highly adapted to low-light conditions and thrive under dense canopy covers. These species rely on shade for optimal growth, often forming the understory layer of mature forests.

Light-Demanding vs. Shade-Tolerant Species

- Light-demanding species grow aggressively in open areas, taking full advantage of available sunlight. However, they struggle in shaded conditions, often becoming stunted or outcompeted by taller trees.

- Shade-tolerant species are adapted to survive under canopy cover, making efficient use of low light intensities. Their slower growth rates are offset by their ability to persist in crowded forests.

- Balanced Forest Growth & Management requires a thorough understanding of these species-specific light needs, ensuring that both natural forests and plantations remain productive and ecologically sustainable.

Here is a table summarizing the characteristics of light-demanding and shade-tolerant species:

Characteristic | Light-Demanding Species (LDS) | Shade-Tolerant Species (SBS) |

Photosynthetic Efficiency | High in full sunlight | Efficient in low-light conditions |

Growth Rate | Rapid under direct sunlight | Slower but sustained in shade |

Leaf Structure | Small, thick leaves with high stomatal density | Large, thin leaves to capture more light |

Survival in Shade | Poor – cannot thrive under canopy | Excellent – adapted to low light |

Root Development | Deep and extensive to access water | Shallow, fibrous for nutrient uptake |

Timber Quality | Often lighter but fast-growing | Dense, high-quality wood |

Successional Stage | Pioneer species in disturbed areas | Climax species in mature forests |

Examples | Teak, Pine, Eucalyptus | Beech, Hemlock, Mahogany |

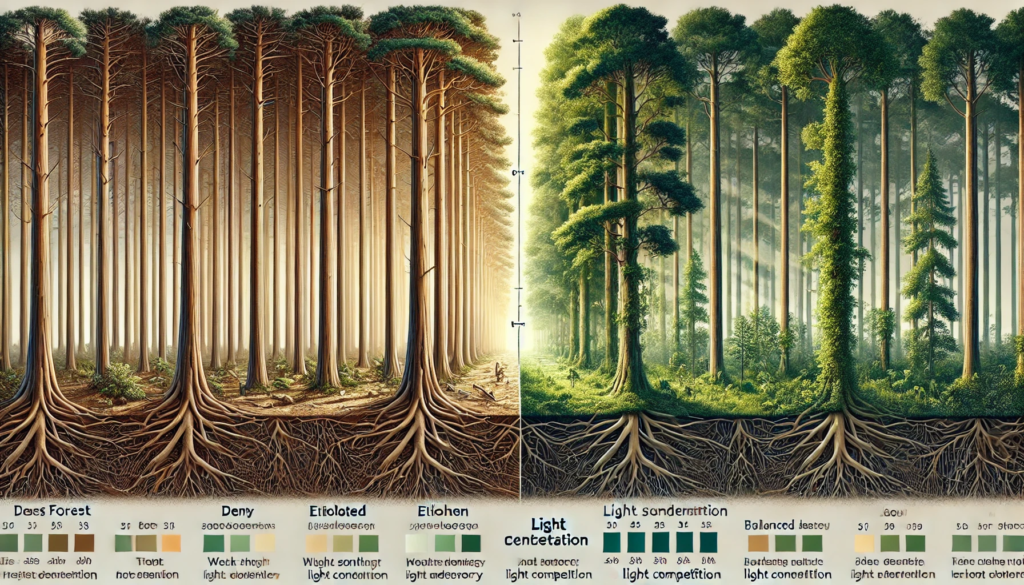

Etiolation and Light Competition

When trees experience insufficient light, they undergo etiolation—a physiological response characterized by elongated, weak stems and sparse foliage as they stretch toward available light. This is commonly observed in dense forests, overcrowded plantations, or poorly managed stands, where competition for sunlight forces trees to grow unnaturally tall and thin, often at the expense of structural integrity.

- Effects of Etiolation: Etiolated trees typically have weaker wood, reduced leaf area, and lower photosynthetic efficiency, making them more susceptible to disease, wind damage, and poor timber quality.

- Light Competition in Plantations: In densely planted forests, trees compete intensely for sunlight, resulting in rapid vertical growth but poor lateral branch development. Without proper management, this can lead to high mortality rates and inferior wood quality.

- Optimizing Light Distribution: Proper stand spacing and selective thinning help maintain a balanced light environment, reducing excessive competition while promoting healthier, more resilient trees.

Photoperiod and Seasonal Growth Cycles

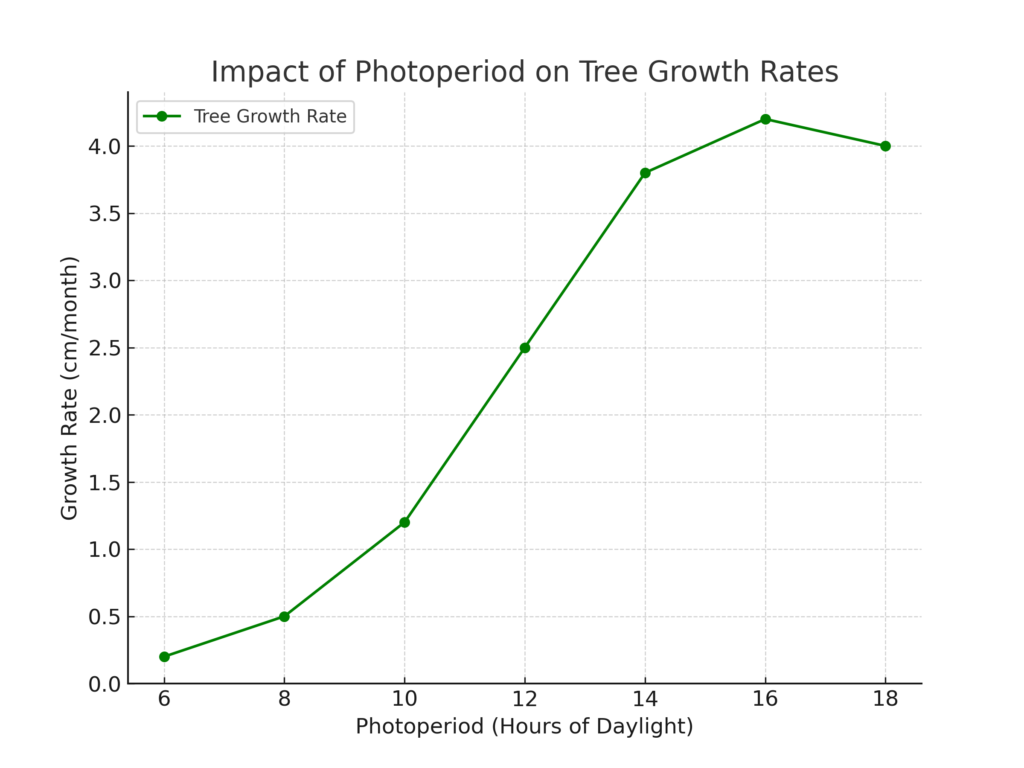

Beyond immediate energy conversion, the duration of daylight exposure—termed photoperiod—plays a pivotal role in regulating seasonal growth cycles. Photoperiod influences fundamental biological processes, including flowering, fruiting, seed germination, and dormancy, ensuring that trees synchronize their reproductive and growth patterns with seasonal changes. This phenomenon is particularly crucial in temperate and boreal forests, where trees must prepare for harsh winters by shedding leaves or slowing metabolic activities.

Understanding these interactions between sunlight, photoperiod, and tree physiology is fundamental for effective forest growth & management and silvicultural practices. By tailoring plantation designs, optimizing stand spacing, and implementing selective thinning techniques, foresters can enhance productivity while maintaining ecological balance. As climate change alters global weather patterns, further research into tree-light interactions will be crucial for developing adaptive forest conservation strategies that ensure sustainability in the years to come.

Understanding Photoperiodism: Nature’s Seasonal Timer

Photoperiodism is the biological mechanism through which plants respond to changes in day length, influencing critical life processes such as flowering, fruiting, and dormancy. This adaptive trait ensures that trees and plants synchronize their growth cycles with seasonal variations, optimizing their survival and reproductive success.

Sunlight serves as more than just an energy source for photosynthesis—it acts as a biological clock that dictates when plants should bloom, bear fruit, or enter dormancy. Different species have evolved specific photoperiodic responses, allowing them to thrive in their native environments.

Here is the graph illustrating the impact of photoperiod on tree growth rates. The graph is generated using AI and following research articles used,-

1. Singh, R. K., Maurya, J. P., & Buschmann, H. (2017). “Photoperiod‐ and temperature‐mediated control of phenology in trees – a molecular perspective.” New Phytologist, 213(2), 511-524.

2. Roeber, V. M., & Bajaj, I. (2021). “The Photoperiod: Handling and Causing Stress in Plants.” Frontiers in Plant Science, 12, 781988.

3. Way, D. A., & Montgomery, R. A. (2015). “Photoperiod constraints on tree phenology, performance and migration in a warming world.” Plant, Cell & Environment, 38(9), 1725-1736.

4. Jackson, S. D. (2009). “Plant responses to photoperiod.” New Phytologist, 181(3), 517-531.

Classification of Plants Based on Photoperiod Sensitivity

Plant Type | Response to Daylight | Examples |

Short-Day (SDP) | Flower when daylight hours fall below a critical limit | Chrysanthemums, Rice, Pineapple |

Long-Day (LDP) | Flower when daylight hours exceed a certain threshold | Spinach, Lettuce, Wheat |

Day-Neutral | Flowering is independent of day length, relying on other factors like temperature | Tomato, Cucumber, Cotton |

(Source: USDA Forest Service, 2019)

Impact of Photoperiod on Flowering and Fruiting

The timing of flowering and fruiting is directly influenced by photoperiod, determining the reproductive success of plants in different climates.

- Short-day plants (SDP): Initiate flowering as daylight hours decrease. These species often bloom in late summer or autumn when nights are longer.

- Long-day plants (LDP): Require longer daylight exposure to flower, making them prominent in spring and early summer.

- Day-neutral plants: Do not rely on daylight duration but instead respond primarily to external factors like temperature, water availability, and overall maturity.

🌿 Examples:

- Strawberries (LDP): Begin fruiting in response to increasing day length in spring.

- Pineapples (SDP): Flower and set fruit as days shorten.

- Tomatoes (Day-neutral): Continue fruiting year-round under suitable conditions, irrespective of daylight duration.

The Role of Photoperiod in Climate Change Adaptation

As climate change disrupts seasonal patterns, shifts in photoperiodic responses could significantly impact plant reproduction and ecosystem stability. Warmer temperatures and unpredictable daylight variations may alter flowering times, disrupt pollination cycles, and affect food production. Understanding these patterns is vital for developing climate-resilient crops and forest species for forest growth that can adapt to these environmental challenges.

By leveraging knowledge of photoperiodism, foresters, botanists, and agricultural scientists can implement strategies such as controlled lighting in greenhouses, selective breeding, and seasonal planning to optimize plant growth and productivity.

Silvicultural Adjustments to Optimize Light Utilization

Stand Spacing and Thinning

Conclusion: Harnessing Solar Radiation for Sustainable Forestry

Proper stand spacing is vital to prevent light competition. In dense plantations, trees grow taller quickly due to light increment, but this can compromise timber quality. Thinning, or selectively removing trees, improves forest growth:

- Light penetration to lower branches.

- Air circulation, reducing the risk of disease.

- Overall tree health and growth rate.

Example: Thinning in pine plantations has been shown to increase timber yield by 30% (USDA Forest Service, 2019).

Water Use and Transpiration

Sunlight affects transpiration, the process where trees lose water through their leaves. Up to 98% of a tree’s water consumption occurs through transpiration. In sunny environments, trees lose moisture rapidly, requiring effective water management to prevent drought stress (FAO, 2020).

Solar radiation and photoperiod are the cornerstones of forest productivity, resilience, and ecological equilibrium. These fundamental drivers regulate photosynthesis, transpiration, growth cycles, and species interactions, shaping the intricate dynamics of forest ecosystems. By understanding the complex interplay between light availability, photoperiodic responses, and tree physiology, foresters can develop adaptive strategies to enhance forest health, optimize timber production, and conserve biodiversity in an era of environmental change.

Strategic Applications in Forestry

- Precision thinning and stand spacing → Mitigating light competition enhances carbon assimilation, radial growth, and wood density, ensuring structural stability and high-quality timber yields.

- Photoperiod-driven afforestation models → Selecting tree species based on their photoperiodic sensitivity supports climate-adaptive reforestation and ecosystem restoration.

- Species-specific canopy management → Balancing light-demanding pioneers with shade-tolerant climax species fosters multi-tiered forest stratification, promoting sustainable biomass accumulation and microhabitat diversity.

- Light availability as a determinant of species richness → Research indicates that gap dynamics in tropical rainforests directly influence seedling recruitment, competitive exclusion, and successional pathways (Journal of Ecology, 2021).

- Photoperiod-mediated dormancy cycles → Regulating seasonal phenophases in boreal and temperate forests ensures species synchronization with pollinators, seed dispersers, and herbivore populations, maintaining functional ecosystem networks.

- Microclimatic buffering under changing light regimes → Forests act as thermal regulators, mitigating temperature extremes and maintaining hydric balance through evapotranspiration fluxes and albedo modulation.

- Remote sensing technologies (LiDAR, UAV-based hyperspectral imaging) allow for real-time monitoring of canopy density, radiation use efficiency (RUE), and net ecosystem exchange (NEE), facilitating precision forestry.

- Dendroclimatology and isotopic analysis provide insights into historical solar radiation variations, aiding in predictive modeling of climate-resilient species selection.

- Genome-assisted tree breeding leverages photoreceptor gene expression studies (e.g., PHYTOCHROME B in conifers) to engineer cultivars with enhanced photosynthetic plasticity and drought tolerance (Nature Plants, 2022).

The Light-Driven Future of Forestry

From managing heliophilic species in expansive plantations to fostering shade-tolerant understory regeneration in closed-canopy systems, light remains a defining force in forest sustainability. By integrating ecophysiological insights with technological advancements, foresters can optimize resource allocation, enhance ecosystem services, and safeguard forests against anthropogenic pressures.

In a world increasingly shaped by climate variability, harnessing the power of solar radiation is not just a scientific endeavor—it is a necessity for the future of global forestry.