Introduction

Forests have played a deeply significant role in India’s history, shaping its landscape, culture, and economy for thousands of years. In ancient times, forests were seen as sacred spaces, closely linked to religious practices, traditional healing systems like Ayurveda, and the livelihoods of sages and hermits who sought solitude in their dense greenery. These forests were not just sources of wood or food; they were homes of wisdom and spirituality, where great epics like the Ramayana and Mahabharata unfolded.

As civilizations advanced, forests became essential for agriculture, trade, and settlement expansion. Over centuries, they provided timber for building palaces, ships, and cities, while also supporting local communities who depended on them for food, medicine, and shelter. However, as human needs grew, so did the pressure on forests.

During British rule, forests faced widespread destruction. Trees were no longer valued for their spiritual or ecological importance but were instead viewed as commercial assets. Vast stretches of forests were cleared to meet the demands of the British empire—whether for laying railway tracks, constructing warships, or establishing large-scale plantations of commercially valuable trees like teak and rubber. The British also introduced laws that restricted the rights of indigenous communities, taking away their traditional access to forests. This period saw forests suffer severe damage, leading to long-term ecological imbalances.

After independence, India took significant steps to protect and restore its forests. Conservation policies, afforestation programs, and wildlife protection laws were introduced to undo the damage of the past and preserve forests for future generations. Today, while India has made remarkable progress in reforestation and biodiversity conservation, challenges such as deforestation, urban expansion, and climate change continue to threaten its green cover.

The story of India’s forests is a powerful reflection of human progress and its consequences. Forests have shaped civilizations, providing shelter, resources, and inspiration, but in return, human actions have also left lasting impacts on them. The way India chooses to manage and protect its forests today will determine the health of its environment and the legacy it leaves for the future.

Forests in the Vedic Period (1500 BCE – 500 BCE)

During the Vedic period, it were deeply intertwined with spiritual, medicinal, and daily life. They were not just landscapes filled with trees but were considered sacred realms where nature and divinity coexisted. Ancient Indian texts like the Rigveda and Atharvaveda describe it as sources of wisdom, healing, and spiritual enlightenment (Sharma, 2001). These scriptures highlight the harmonious relationship between humans and forests, emphasizing the importance of preserving nature for both material and spiritual well-being.

Classification of Forests in Vedic Literature

Classification of Forests in Vedic Literature

Vedic texts categorized forests based on their function and significance in human life:

- Tapovan – Sacred groves where sages and ascetics meditated, performed penance, and sought enlightenment. These forests were untouched by human exploitation and were seen as places of divine energy.

- Mahavan – Large, untamed forests that were preserved in their natural state. These dense forests were home to wildlife and were considered essential for maintaining ecological balance.

- Shrivan – Forests that were managed and cultivated by humans for their daily needs. These forests provided food, fuelwood, medicinal herbs, and other resources, ensuring sustainable human survival.

Woodland as Centers of Knowledge & Healing

Woodland as Centers of Knowledge & Healing

Forests in the Vedic era were not just habitats for flora and fauna but were living classrooms where sages discovered the secrets of nature. Ayurveda, India’s ancient system of medicine, was developed through an intimate understanding of forest plants and their healing properties (Dash & Kashyap, 1987). Trees like Peepal (Ficus religiosa), Banyan (Ficus benghalensis), and Neem (Azadirachta indica) were revered not only for their spiritual symbolism but also for their medicinal benefits.

The Vedic way of life was deeply eco-centric, advocating for coexistence with nature rather than exploitation. This reverence for woodland ensured that they were protected, nurtured, and sustainably used, forming the foundation of India’s early environmental consciousness.

Forests in the Maurya & Gupta Periods (321 BCE – 550 CE)

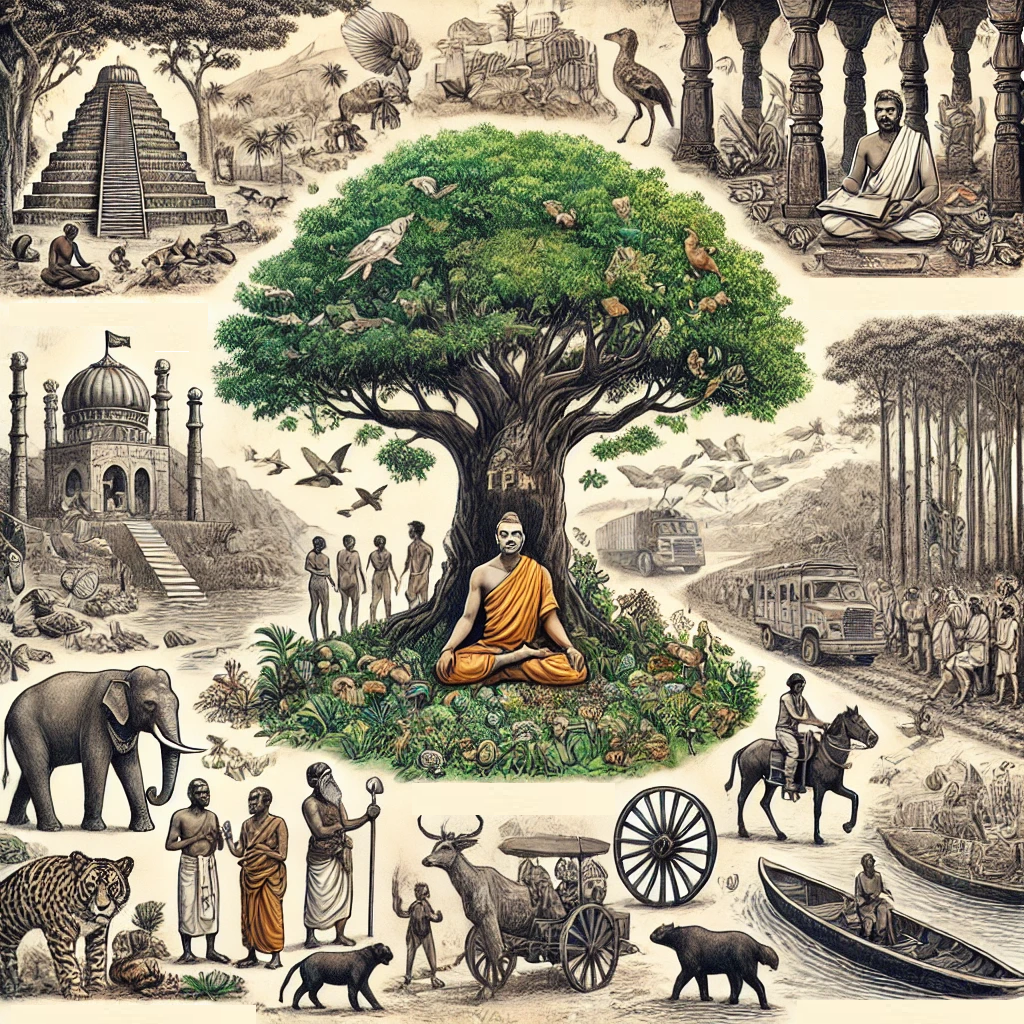

As Indian civilization advanced, the importance of woodland extended beyond just spiritual and medicinal purposes to organized management and governance. The Maurya Empire (321–185 BCE) was one of the first to recognize forests as a valuable resource that needed protection, regulation, and sustainable use. Under the guidance of Kautilya (Chanakya), the chief advisor to Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, forest conservation became an essential part of state administration. In his influential text, the Arthashastra, Kautilya emphasized that forests were not just a source of timber but also critical for economic stability, military strength, and environmental balance (Rangarajan, 1992).

🌳 Key Developments in Woodland Management During the Maurya Period:

- Establishment of the Vanadhyaksha (Forest Superintendent): The Mauryas created the position of a Vanadhyaksha, an official responsible for overseeing forest conservation, timber production, and wildlife protection. This was one of the earliest recorded examples of state-controlled forestry.

- Regulated Timber Harvesting: Unlike unregulated deforestation, the Mauryas introduced strict laws to ensure that trees were cut in a sustainable manner, preventing excessive depletion of forest resources.

- Wildlife Protection Policies: Forests were home to elephants, lions, and other wildlife, which were considered valuable for military use, agriculture, and trade. The Mauryas took steps to protect elephants, as they were essential for warfare and transportation. Elephant forests (Hastivanas) were designated, ensuring that these majestic animals could thrive.

The Mauryan rulers understood that forests were essential for the long-term survival of their empire—providing materials for infrastructure, medicine for healing, and wildlife for economic and military purposes.

Forests in the Gupta Period (4th–6th Century CE)

Following the Mauryan legacy, the Gupta Dynasty also recognized the value of forests, though their approach was more focused on agricultural expansion and beautification. The Guptas encouraged tree planting along roads, village boundaries, and temple complexes to provide shade, improve air quality, and enhance aesthetic beauty (Thapar, 2000).

- Roadside Afforestation: The Guptas promoted the planting of fruit-bearing and medicinal trees along highways to benefit travelers and local communities.

- Village & Temple Groves: They supported the creation of green spaces near villages and temples, where trees were often planted in sacred groves, reinforcing the cultural and religious connection to nature.

- Balancing Agriculture & Forestry: While the Guptas expanded agriculture, they ensured that forests were not entirely cleared, maintaining a balance between farmland and woodland conservation.

This period marked a shift from strict state control to a more community-driven approach, where local rulers, village leaders, and religious institutions took responsibility for protecting and maintaining forests.

Legacy of Ancient Indian Forest Management

Both the Maurya and Gupta periods laid the foundation for sustainable forestry practices in India. They understood that forests were not just a resource to exploit but a treasure to preserve. The careful balance between conservation and utilization set a precedent for later environmental policies. These early efforts remind us that forests have always been central to India’s survival, prosperity, and cultural identity—a lesson that remains just as relevant today. 🌿✨

Forests in the Medieval Period (600 CE – 1700 CE)

With the arrival of Islamic rulers in India, forest management and land use patterns underwent significant changes. Unlike the Vedic and Mauryan periods, where forests were largely preserved for religious, medicinal, and economic reasons, the medieval era saw forests being cleared to support urban expansion, military needs, and agriculture. The demand for timber, fuelwood, and land increased as empires grew, resulting in widespread deforestation (Lal, 1995).

🏰 Effects of Medieval Rule on Forests

- Large-Scale Deforestation for Urban Expansion

- The construction of forts, palaces, mosques, and cities required vast amounts of timber and land.

- Forests were cleared to make space for new settlements, roads, and irrigation projects.

- As agriculture became the backbone of the economy, more fertile land was reclaimed from forests, reducing green cover.

- Use of Timber for Shipbuilding & Military Needs

- Timber from forests was in high demand for warships, artillery, and cavalry equipment.

- The Mughal navy under Babur and Akbar relied on strong teak and sal wood for building fleets used in river and coastal battles.

- Wood was also extensively used for weapon storage, gun carriages, and defensive structures.

- Impact on Indigenous Communities & Tribal Conservation

- While large-scale deforestation took place, many tribal and forest-dwelling communities continued their traditional conservation practices.

- Indigenous groups resisted deforestation by maintaining sacred groves and sustainable hunting methods.

- However, as forests shrank, these communities faced displacement and restrictions on their access to forest resources.

🌳 The Mughal Contribution: Gardens & Green Spaces

Despite the environmental pressures of deforestation, the Mughals recognized the importance of trees and green spaces. Inspired by Persian and Central Asian traditions, they developed elaborate gardens, often located within palace complexes, tombs, and public areas.

- Akbar (1556–1605 CE) promoted tree planting for shade, fruit production, and aesthetics, encouraging afforestation in urban centers.

- The famous Mughal Gardens, such as those at Shalimar Bagh (Kashmir) and Mehtab Bagh (Agra), showcased the beauty of landscaped forestry.

- Emperor Jahangir (1605–1627 CE), an avid nature lover, documented tree species and wildlife, promoting early environmental awareness.

The medieval period was a time of both destruction and preservation for India’s forests. While deforestation increased due to empire-building and agricultural expansion, rulers like Akbar and Jahangir also promoted tree planting and green urban spaces. The balance between exploitation and conservation during this time foreshadowed future challenges in managing forests sustainably. 🌿🏰✨

Forests Under British Rule: Exploitation & Consequences (1757 – 1947 CE)

The British colonial era marked a turning point in India’s forest history. Unlike earlier rulers who saw forests as sacred spaces or sources of sustenance, the British viewed them purely as commercial assets. Forests were not protected for their ecological value but were exploited on an industrial scale to meet the demands of the British Empire (Gadgil & Guha, 1992). The shift from traditional, community-based forest management to state-controlled forestry led to widespread deforestation, biodiversity loss, and displacement of indigenous communities.

🌲 Key Impacts of British Rule on Indian Forests

1. Large-Scale Deforestation for Railways & Shipbuilding

The expansion of British-controlled railways and naval fleets led to massive destruction of India’s forests.

- Millions of trees were cut down to make railway sleepers, as wood was the primary material used to support railway tracks (Stebbing, 1923).

- Timber was extensively used for building warships, docks, and naval stations for the British navy.

- Forests in regions like Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and the Western Ghats were cleared on a massive scale to supply teak and sal wood for these purposes.

- The construction of roads, bridges, and colonial settlements further accelerated deforestation.

By the late 19th century, the destruction was so severe that many regions faced timber shortages, forcing the British to rethink their forest policies.

2. The Indian Forest Act (1865, Revised in 1878 & 1927)

The Indian Forest Act was one of the most controversial policies imposed by the British. It shifted control of forests from local communities to the colonial government.

- The 1865 Act allowed the British to declare forests as government property, stripping tribal communities of their traditional rights to use forest resources (Guha, 1989).

- The 1878 revision divided forests into Reserved Forests, Protected Forests, and Village Forests, heavily restricting local people’s access to timber, firewood, and grazing lands.

- The 1927 Act further strengthened colonial control, criminalizing traditional practices like shifting cultivation and community harvesting.

This legal framework alienated forest-dependent communities, turning them into trespassers on lands they had lived on for generations.

3. Introduction of Commercial Plantations

The British introduced monoculture plantations, replacing diverse native forests with commercially valuable trees such as teak, sal, and rubber.

- These plantations catered to British industries, providing raw materials for timber, paper, and rubber production.

- The shift to monocultures drastically reduced biodiversity, affecting native flora and fauna.

- Many forests lost their natural regeneration ability, leading to long-term ecological damage.

This profit-driven forestry approach ignored traditional Indian conservation methods, prioritizing revenue generation over environmental balance.

4. Displacement of Tribal & Indigenous Communities

For centuries, tribal communities had lived harmoniously with forests, practicing sustainable hunting, gathering, and shifting cultivation. Under British rule, these communities faced forced eviction and loss of livelihoods (Shiva, 1988).

- Large tracts of forests were declared government property, leaving indigenous people landless and powerless.

- Many were pushed into poverty as their traditional sources of food, medicine, and shelter were taken away.

- Some tribes resisted through local uprisings, such as the Santhal Rebellion (1855-56) and the Munda Revolt (1899-1900), but these were brutally suppressed by the British.

By the early 20th century, British forest policies had irreversibly changed the relationship between people and forests, replacing community-led conservation with strict colonial regulations.

The Beginning of Scientific Forestry

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, British officials realized that their exploitative policies were causing severe ecological damage. In response, they introduced scientific forestry practices, largely influenced by European models.

- Dietrich Brandis, a German botanist, was appointed as the first Inspector General of Forests in India in 1864 (Ribbentrop, 1900).

- He established forest research institutions and trained foresters in methods like controlled logging and afforestation.

- The Imperial Forest Department was created to regulate timber harvesting and promote forest conservation—but the primary goal remained economic gain rather than ecological balance.

Though scientific forestry helped prevent total deforestation, it was still focused on maximizing timber output for British industries, rather than restoring forests for biodiversity or local communities.

The British colonial era was a time of massive environmental degradation and social upheaval for India’s forests. While it introduced scientific forestry, it also led to large-scale deforestation, biodiversity loss, and the alienation of tribal communities.

The legacy of British forest policies can still be felt today—many of India’s forest laws, conservation strategies, and land-use policies have roots in the colonial model. However, the post-independence era brought new reforms, aiming to restore forests, protect wildlife, and recognize indigenous rights.

India’s forests, once seen as sacred and self-sustaining ecosystems, were transformed into commercial commodities under British rule. Yet, despite these challenges, India has worked towards reclaiming its forests, promoting afforestation, and integrating traditional conservation wisdom with modern science. 🌿✨

Post-Independence Forest Policies (1947 – Present)

Forest Conservation in Post-Independence India

After gaining independence in 1947, India faced a critical challenge—balancing economic growth with environmental conservation. Decades of colonial exploitation had left vast areas of forests degraded or completely destroyed. Recognizing the vital role forests play in maintaining ecological stability, the government introduced several policies and laws to protect and restore forest cover while ensuring sustainable development.

📜 Major Developments in Forest Conservation

- Forest Policy of 1952: Acknowledging Ecological Importance

The first major post-independence forest policy was introduced in 1952, emphasizing the role of forests in maintaining ecological balance. It marked a shift from commercial exploitation (as practiced under British rule) to a national approach focused on conservation. However, the policy still leaned towards timber production, and its implementation remained weak.

- Forest Conservation Act, 1980: Controlling Deforestation

By the late 1970s, rapid industrialization, urban expansion, and agricultural land conversion had led to mass deforestation. To curb this, the Forest Conservation Act, 1980 was enacted (MoEF, 1980). This law:

✅ Banned deforestation for non-forest activities without prior government approval.

✅ Required compensatory afforestation when forest land was diverted for projects.

✅ Empowered the central government to oversee and regulate forest use.

This Act was a landmark step in strengthening forest protection but still needed community participation to be truly effective.

- National Forest Policy, 1988: A Shift Towards Sustainability

The 1988 National Forest Policy (MoEF, 1988) marked a major turning point, shifting the focus from commercial forestry to sustainable forest management. Key highlights include:

🌿 Emphasis on biodiversity conservation over timber production.

🌿 Recognition of tribal rights and the importance of local communities in forest management.

🌿 Encouragement of afforestation and eco-restoration programs.

This policy paved the way for community-driven conservation efforts, particularly Joint Forest Management (JFM).

🌍 Joint Forest Management (JFM): Empowering Communities

One of the most revolutionary conservation efforts in post-independence India was the Joint Forest Management (JFMC) program in the 1990s. This initiative was based on the understanding that forests cannot be conserved without the participation of local communities—the very people who depend on them for survival.

How JFM Works

- Under this model, the government and local communities share the responsibility of protecting and regenerating forests.

- JFM Committees (formerly known as Forest Protection Committees) were set up at the village level, consisting of local villagers and forest officials.

- These committees were given legal backing and tasked with monitoring forest health, preventing illegal activities (like logging and encroachment), and promoting afforestation.

- In return, the communities were granted rights to use minor forest produce (like fruits, fodder, and medicinal plants) and a share of timber revenues from protected forests.

Impact of JFM on Forest Conservation

✅ Increased forest cover & regeneration – JFM successfully helped restore degraded forests across India.

✅ Reduced conflicts between locals & forest officials – By giving people a stake in conservation, JFM built trust and cooperation between communities and the government.

✅ Improved livelihoods – Villagers could legally collect firewood, fodder, and medicinal plants, providing them with sustainable incomes.

✅ Better forest protection – With locals acting as protectors, instances of illegal logging and poaching declined in many areas.

Despite its success, JFM faces challenges, including bureaucratic hurdles, lack of proper funding, and conflicts over benefit-sharing. However, it remains one of India’s most significant grassroots conservation efforts.

- Wildlife Protection Act, 1972: Preserving India’s Biodiversity

Recognizing the alarming decline in wildlife populations, the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 was passed. This law:

🦁 Established protected areas, including national parks, wildlife sanctuaries, and biosphere reserves (Singh, 1993).

🦅 Prohibited hunting and poaching of endangered species.

🦏 Created the foundation for conservation projects like Project Tiger (1973) and Project Elephant (1992).

This Act remains India’s strongest legal safeguard for protecting its rich biodiversity.

- Afforestation & Reforestation Efforts

Recognizing the need to restore lost green cover, the Indian government launched several afforestation programs, including:

🌱 Social Forestry Programs – Encouraging tree planting in non-forest areas, including farmlands and urban spaces.

🌱 Compensatory Afforestation Programs – Ensuring new forests are planted when old ones are cleared for development.

🌱 Green India Mission (2014) – A large-scale initiative aimed at expanding India’s forest cover and improving ecosystem services.

🌍 Current Status of Indian Forests

According to the Forest Survey of India (FSI, 2023):

- Forest Cover (2023): About 21.71% of India’s land is covered by forests.

- Increase in green cover: Since independence, afforestation efforts have helped stabilize forest loss.

- Threats to forests remain: Illegal logging, encroachments, climate change, and urbanization continue to put pressure on forests.

Solutions for a Sustainable Future

To ensure a greener future, India is focusing on:

✅ Agroforestry & Sustainable Land Use – Integrating tree planting with agriculture to balance farming and forest conservation.

✅ Stronger Legal Protections – Enforcing stricter penalties against illegal deforestation and poaching.

✅ Eco-Tourism & Community-Based Conservation – Promoting sustainable tourism to generate revenue while preserving biodiversity.

✅ Technology & AI in Forest Monitoring – Using satellite imagery and artificial intelligence to track forest health and illegal activities.

Since independence, India has made significant progress in forest conservation, but challenges remain. Initiatives like the Forest Conservation Act, Joint Forest Management, and afforestation programs have helped reverse some of the damage done during colonial rule. However, the future of India’s forests depends on collective action—government policies, local community participation, and public awareness.

Protecting forests isn’t just about saving trees—it’s about preserving biodiversity, ensuring climate stability, and securing livelihoods for millions. 🌎🌿✨

Current Status of Indian Forests:

- Forest Cover (2023): About 21.71% of India’s land is forested (FSI, 2023).

- Challenges: Illegal logging, land encroachments, climate change, and biodiversity loss.

- Solutions: Agroforestry, afforestation, eco-tourism, and stricter conservation laws.

Conclusion

India’s forests have witnessed an extraordinary journey—from being revered as sacred spaces in ancient times to suffering rampant deforestation during British rule, and finally, to gradual revival efforts in the post-independence era. For centuries, forests were seen as more than just trees and land—they were sources of life, wisdom, and sustenance, deeply embedded in Indian culture, spirituality, and traditional knowledge systems. However, with the advent of colonial rule, forests were reduced to mere commercial assets, leading to large-scale destruction that disrupted both ecosystems and indigenous communities.

In the years following independence, India recognized the need to restore and protect its forests. Conservation policies, afforestation programs, and wildlife protection laws have helped rebuild forest cover, but challenges remain. Rapid urbanization, industrial expansion, illegal logging, and climate change continue to threaten India’s green landscapes. Despite legal safeguards, forests are still being cleared for infrastructure, agriculture, and commercial activities, making it clear that policy alone is not enough—active participation from communities, conservationists, and policymakers is crucial.

The future of India’s forests depends on a sustainable, people-centric approach. Empowering local communities through participatory conservation, strengthening forest protection laws, and integrating modern technology like satellite monitoring and AI-driven forest management can ensure that these precious ecosystems thrive for generations to come. Forests are not just a resource to be used—they are a part of our heritage, a shield against climate change, a home for wildlife, and a source of life for millions. Their protection is not just an environmental necessity but a moral responsibility—one that will shape the health of our planet and the well-being of future generations. 🌿🌍✨

What are the classification of forests in vedic literature?

- Tapovan – Sacred groves where sages meditated, practiced penance, and pursued enlightenment.

- Mahavan – Vast, wild forests preserved in their pristine natural state.

- Shrivan – Forests cultivated and managed by humans for daily sustenance.

What leads to massive destruction of India's forests during the British colonial rule?

- Commercial Logging for Railways – Large-scale deforestation occurred to meet the demand for timber, especially sal and teak, for railway sleepers and bridges.

- Timber Extraction for Shipbuilding – The British navy heavily relied on Indian hardwoods, particularly teak, for constructing warships.

- Expansion of Cash Crop Plantations – Vast forested areas were cleared to establish tea, coffee, and rubber plantations for export.

- Revenue-Oriented Forest Policies – The Indian Forest Act of 1865 and 1878 restricted local access to forests and prioritized British economic interests.

- Destruction for Agriculture – The British promoted large-scale deforestation to expand revenue-generating agriculture, especially for indigo, cotton, and jute.

- Hunting and Game Reserves – The British elite engaged in excessive hunting, leading to habitat destruction and loss of biodiversity.

- Shift from Community Management to State Control – Traditional forest management by local communities was dismantled, leading to unchecked exploitation.

- Deforestation for Military Needs – Timber was heavily extracted for making weapons, building cantonments, and supporting war efforts, especially during World Wars.

- Neglect of Ecological Balance – The British policies focused solely on profit, disregarding the environmental and ecological impact of deforestation.

Who was a noted environmentalist and expert in forest management and is known to be the father of the concept of Joint Forest Management, often abbreviated as JFM?

Silviculturist Dr. Ajit Kumar Banerjee, IFS (Bengali: ড. অজিত কুমার ব্যানার্জী) (1 September 1931 – 29 November 2014)