Introduction:

Silviculture, the science and practice of forest management, is heavily influenced by climatic conditions, among which thermal level or ambient heat energy plays a fundamental role (Larcher, 2003). Thermal conditions affects tree growth, regeneration, species distribution, and overall forest health. Understanding how temperature interacts with other climatic elements allows foresters to develop sustainable management strategies, ensuring the resilience and productivity of forest ecosystems (Bolte et al., 2010).

Temperature:

Temperature i.e. Thermal Condition is a fundamental climatic factor that influences tree physiology at multiple levels, from cellular metabolic processes to individual tree biology and, ultimately, forest ecosystem dynamics. Trees, being stationary organisms, must adapt to Thermal conditions fluctuations to survive, grow, and reproduce. Understanding the role of ambient temperature in tree physiology is essential for silvicultural practices, afforestation, and sustainable forest management, especially in the face of climate change.

This article explores how Thermal conditions affects tree physiology, starting at the cellular level and extending to whole-tree biology and forest management strategies.

Temperature at the Cellular Level: Biochemical and Metabolic Processes

At the cellular level, Thermal level influences enzymatic activities, respiration rates, and photosynthetic efficiency. Trees, like all plants, depend on complex biochemical reactions that are sensitive to thermal gradient.

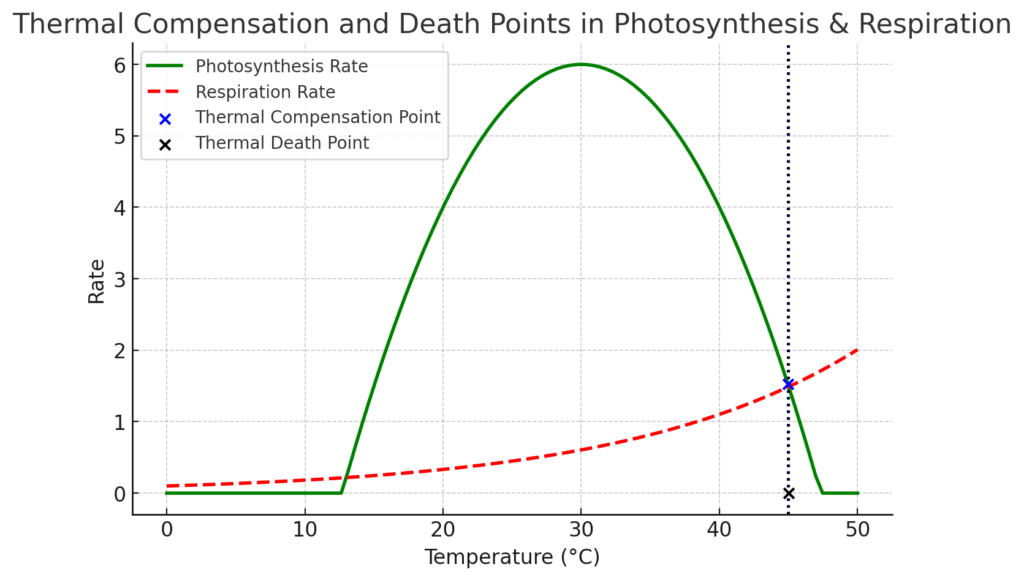

Photosynthesis & Respiration:

Photosynthesis:

Thermal conditions directly impacts the efficiency of photosynthesis by affecting enzyme activity, particularly that of RuBisCO (Ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase-oxygenase), the key enzyme in carbon fixation.

- Optimal Thermal Regime: Most tree species have an optimal thermal regime for photosynthesis. For example:

-

- Tropical species: 25–35°C

- Temperate species: 15–25°C

- Boreal species: 5–15°C

-

High Thermal conditions (above the optimum) cause enzyme denaturation, reducing photosynthetic efficiency. Low temperatures (below the optimum) slow down enzyme activity, leading to reduced carbon fixation.

Respiration:

Cellular respiration releases energy from stored carbohydrates to support growth, reproduction, and survival (Atkin et al., 2005).

As Thermal conditions increases, respiration rates rise exponentially, leading to higher energy consumption. However, if respiration outpaces photosynthesis (due to extreme heat), trees may experience carbon starvation, leading to reduced growth or even mortality.

Warmer temperatures generally enhance photosynthesis up to an optimal limit, beyond which enzymatic activities decline, reducing plant productivity (Way & Yamori, 2014).

Respiration rates increase with temperature, affecting carbon sequestration and biomass accumulation (Atkin et al., 2005).

Protein Function and Heat Shock Response

Extreme temperatures cause protein misfolding or denaturation. To counteract this, trees produce heat shock proteins (HSPs) that help refold damaged proteins and protect cellular integrity. In cold conditions, trees enhance the production of antifreeze proteins (AFPs) to prevent ice crystal formation in cells.

Water Balance and Membrane Stability

Thermal condition affects cell membrane fluidity.

- At high Thermal conditions, membranes become too fluid, leading to ion leakage and cell damage.

- At low Thermal conditions, membranes stiffen, impairing nutrient transport and metabolic reactions.

Stomatal regulation is also temperature-dependent, influencing transpiration rates and overall tree hydration.

Temperature Effects on Individual Tree Growth and Wood Quality

Temperature influences key aspects of tree growth, including seed germination, root development, cambial activity, timber quality and reproductive cycles.

Seed Germination and Dormancy

Each tree species has a specific Thermal regime required for successful seed germination.

- Cold stratification: Many temperate and boreal species (e.g., oaks, maples) require a period of chilling (0–5°C) to break dormancy and stimulate germination (Cardinal Temperature).

- Heat-triggered germination: Some species (e.g., certain pines and eucalyptus) require exposure to fire or high thermal conditions to break seed dormancy.

Thermal conditions influences seed dormancy and germination success (Fenner & Thompson, 2005). Many tree species require a specific thermal range for optimal seedling emergence.

Extreme cold can delay germination, while excessive heat may lead to desiccation or reduced viability (Baskin & Baskin, 2014).

Cardinal Temperature

Cardinal temperature refers to the three critical Heat levels points—minimum, optimum, and maximum—that influence the growth and physiological activities of plants, including trees in silviculture. These temperatures define the range within which a plant can survive, grow, and reproduce effectively.

- Minimum Thermal conditions: The lowest temperature at which a plant can sustain basic physiological functions without suffering damage.

- Optimum Thermal conditions: The ideal thermal regime where growth and metabolic activities are at their peak.

- Maximum Thermal conditions: The highest ambient temperature beyond which plant cells suffer irreversible damage, leading to reduced growth or death.

Factors Affecting Cardinal Temperature

-

Species Variation: Different plant species have unique cardinal temperature ranges based on their genetic adaptations. For example, tropical trees have higher optimum Thermal conditionscompared to temperate species.

-

Latitude and Altitude: Thermal conditions decreases with increasing latitude and altitude, affecting plant distribution and growth patterns.

-

Seasonal Changes: Fluctuations in temperature across seasons influence seed germination, dormancy, and overall tree development.

-

Soil Temperature: The Thermal conditions of the soil affects root growth, microbial activity, and nutrient availability, thereby impacting plant health.

-

Moisture Availability: Adequate moisture can help plants withstand higher Thermal conditions, while drought conditions can exacerbate heat stress.

-

Solar Radiation: Direct sunlight exposure influences Climatic warmth regulation in plants through processes like photosynthesis and transpiration.

-

Wind and Air Circulation: Wind affects thermal conditions by increasing heat loss through evaporation and convection, which can either cool or stress plants.

-

Human Activities: Deforestation, urbanization, and climate change contribute to thermal conditions variations that alter the cardinal temperature limits of many species.

Root Growth and Water Uptake

Root growth is highly sensitive to Thermal gradient.

- Optimal range: 10–25°C for most species.

- Cold soils: Slow down root elongation and reduce water uptake, making trees more vulnerable to drought stress.

- Extreme heat: Increases root respiration, leading to energy depletion.

Cambial Activity and Wood Formation

The vascular cambium, responsible for secondary growth (wood formation), is temperature-dependent.

- Active cambial growth occurs in warmer months and slows or ceases in winter.

- Higher Thermal conditions can accelerate growth but may also lead to reduced wood density, affecting timber quality.

Reproductive Cycles and Flowering

Climatic warmness or coolness influences flowering time and fruit production.

- Warmer temperatures: Can lead to early flowering, which may disrupt synchronization with pollinators.

- Cold temperatures: May delay flowering, affecting seed set and fruit development.

Temperature at the Forest Level: Large-Scale Impacts and Management Strategies

At the ecosystem level, Thermal conditions shapes forest composition, productivity, and resilience to climatic stressors.

Impact of Thermal Level Extremes on Forest Management

Frost and Cold Stress:

- Frost damage is a major concern in temperate and high-altitude forests, leading to tissue damage and slowed growth (Sakai & Larcher, 1987).

- Tree species with higher cold tolerance (e.g., Pinus spp.) are preferred in regions prone to frost (Prasad et al., 2006).

Heat Stress and Drought:

- Rising Thermal conditions, coupled with reduced moisture availability, cause heat stress, leading to wilting, leaf scorch, and increased susceptibility to pests (Allen et al., 2015).

- Adaptive silvicultural techniques, such as mixed-species plantations and drought-resistant tree selection, help mitigate these effects (Adaptivesilviculture.org).

Forest Fire Risks

Rising Thermal conditions contribute to increased wildfire frequency and intensity. Dry conditions and heat waves create ideal conditions for fire ignition and spread. Some fire-adapted species, such as Pinus ponderosa, rely on periodic fires for regeneration. Silvicultural fire management techniques include prescribed burning, thinning, and creating firebreaks to mitigate risks.

- Higher Thermal conditions contribute to increased evapotranspiration and drier fuel conditions, elevating wildfire risks (Bowman et al., 2020).

- Effective forest management includes controlled burning, firebreaks, and species selection to enhance fire resistance (Vox.com).

Phenology and Growing Seasons

Warmer Thermal conditions lead to longer growing seasons, potentially increasing forest productivity. However, heat stress and water limitations may offset these gains, leading to reduced carbon sequestration.

Adaptive Silvicultural Strategies for Temperature Management

To mitigate the effects of temperature fluctuations on forests, silviculturists employ various adaptive strategies. With global climate change altering Thermal patterns, foresters must integrate adaptive strategies to ensure sustainable forest management (IPCC, 2021). Key approaches include:

- Species selection: Choosing climate-resilient species suited to local temperature conditions. Selecting climate-resilient species is suited to projected temperature variations (Bolte et al., 2009).

- Assisted migration: Relocating tree species to areas with favorable temperature conditions. Implementing assisted migration by relocating species to suitable climatic zones (The Guardian).

- Forest thinning and stand management: Enhancing air circulation and reducing competition for water in high-temperature regions.

- Soil and water conservation: Mulching, irrigation, and maintaining ground cover to reduce heat stress. Enhancing soil moisture conservation through mulching, contour planting, and improved irrigation techniques (Chaves et al., 2003).

- Genetic improvement programs: Developing temperature-tolerant tree varieties through selective breeding.

- Adjusting planting schedules to align with optimal growing conditions.

Conclusion:

Temperature is a key driver of tree physiology, influencing processes from the cellular level to whole-tree growth and forest ecosystem dynamics. While trees have evolved various adaptations to cope with Thermal conditions fluctuations, climate change is altering traditional thermal regimes, posing challenges to forest sustainability. Silviculturists must employ adaptive strategies, such as species selection, stand management, and water conservation, to ensure forest resilience in a warming world.

By understanding the intricate relationship between temperature and tree physiology, we can develop more effective silvicultural practices, contributing to sustainable forestry and ecological balance.